Ethiopia, Notes & Photos.

For some reason to me Ethiopia sounds closer than it actually is. Northern Africa. Even for a geographer it seems like it’s not too far from Europe… And yet, to get to Addis Ababa from Missoula, Montana is a 8220 miles journey, give or take.

Just another day. Early morning. TSA lines. Stale air. Airplane food. Cramped legs. Airplane bathrooms. Airport benches. Are these even benches? Denver. Frankfort. It all begins to blur somewhere along the way. You fly over light and dark and light again, but my body is just simply confused and I don’t know which is which. I try to read. I read a little. Mostly fall asleep to bad movies that never find their way to the surface of Netflix at home. Finally, the captain says we are coming close. I hear the wheels come down. My mind sparks a little. This is the excitement of travel. This is the familiar unfamiliarity. Twenty two hours later I’m on the ground.

In the bustle of a new airport my mind tracks through the expected protocol that is the same and different in every country. In every country you first will find the bag carousel. Customs. Money exchange. Then the chaos of the exit terminal. In every developing country I’ve ever been to the scene is the same. Hundreds if not millions of taxi and car drivers, some official, many not, who are vying for your ride. The voices tumbling over each other, arms flashing, waving, come with me, I take you to best hotel, you need a ride? And so it begins.

But it is different here. Everything is a little more relaxed. Customs is the easiest I’ve ever passed through with the exception of Nepal. They seemed legitimately pleased to have a visitor (take note TSA & US Customs… It is ok to actually welcome people) and after a simple line I am on my way out to the swarm of taxis, except when I walk out the door, mentally prepared for the bombardment, there is not one. Taxis and public transport are all down the sidewalk a bit, giving every passenger a bit of a buffer before the chaos. A welcome buffer. I set my bag down and mentally smoke the cigarette that would be appropriate to roll and smoke right now if I were a smoker. Thank goodness I’m not. There is ample diesel fumes in the air.

The sun hits me. It’s bright. Montana is mid-winter, near its darkest day of the year. This feels like the other side of the world. There is the familiar international smell of diesel in the air. The sound of a billion bees, or is it traffic? But all muted by the glare of the bright sun, shining potently through the layer of haze that I presume to be smog. Kathmandu. Lima. Managua. L.A., Mexico City. Even Missoula on a bad day. But it feels good and I stuff my long sleeve into my backpack while I look around.

I check my non-connected cell phone to find a picture of the name of the hotel name I am to go to, but when I enter the crowded sidewalk below I see a familiar face waving to me and easier than I’d ever have imagined I am in a car going to the hotel. I’m here with Sustainable Harvest and the head roaster of Water Avenue. We’ve been picked up by Abiy, whom I later come to realize is much more than your standard human, he is a bridge, a bridge that spans not only oceans but time and who connects with people on a level rare in this world. Truly the inspiration of a global citizen, it is with Abiy that I first came to the idea that nationality is an antiquated concept that we are due to abandoned in this world of modern trade, travel, and human movement.

The hotel is nice. Fancy by some measures. Shiny. As soon as I’m in the room my body wants to collapse, but I know I have miles to go before I’ll get a chance to sleep. I set a timer on my phone. 15 minutes. No 20. But I can’t even lay down. My mind is too excited. I pull out my coffee kit which is designed for this very moment. With a 220-volt water immersion coil, I heat water in my water bottle, porlex grind, French press. To the porch to take it in. My first coffee in country. This is often my favorite or at least most memorable in every country I’ve ever been to. As the first sip hits, standing on a balcony, overlooking a new city, a new country, a new adventure, looking out across a new landscape, the sound of traffic familiar and new at the same time, the sounds of morning, the smells of traffic and movement and food and sewage. Dust. People carrying things like they never do in the states. Big piles and tarps of things. Cars and vans flowing through unregulated traffic. Construction. Half complete, half-abandoned. Congestion. Homeless. Suits and ties. Police. Delivery trucks with strapped on loads hanging off the side. Bike loads of unfathomable size, like elephants riding a tricycle. I’d love to lay down for twenty minutes, but there’s not a chance. My brain is too wired I just want to take this all in and then go get in it.

We meet in the lobby. Basic introductions. Water to drink. Jill, from Water Ave, who also just arrived, has the same glazed look I feel in my brain. But the desire to be awake is enough to keep us going, regardless of what my body is telling me. Which is that it is midnight two days since I’ve had a good night’s sleep… the weird nature of jet lag.

Abiy has a slide show on his laptop. We find a quiet corner and he goes through the hierarchy and pathways of coffee from farm to export, a process that takes naturally growing and farmed coffee from small and large properties alike, processes them, and transports them first to Addis, then to Djibouti for its journey across the ocean to market. Abiy is organized in a corporate style of the Hague which he calls home, but his Levi’s and casual jacket tell there is more to the story. It is his side notes that are the most interesting.

Abiy was raised in rural Ethiopia. His father was a priest who moved from the politically powerful north to the western side of the country in order to provide a living ample enough to send his children to university. His father has since passed, but his mother and sister live in Addis now, and he has other family scattered across northern Europe and the US.

And as casual as he is, Abiy is a masterful planner, able to create clear pathways of accomplishing things that do not follow straight lines, but rather the fluid lines necessary to get around in a bustling, quite chaotic city of approximately 4 million people. Addis Ababa has nearly doubled in the last 10 years, and he has been able to keep up and make the complications of living between two worlds seem easy. This is one of the world’s fastest-growing populations. And it feels like it.

Half tired, completely jet-lagged, but running on the excitement of the first day, we load into Abiy’s car and set off for our first stop. We’ll be seeing things a little in reverse in terms of the coffee plot of Ethiopia. We are first visiting one of the largest dry mill facilities in Ethiopia. Coffee from around the country makes it’s way here and similar mills in semi-trucks, loaded in 200-pound bags to be dry milled. Dry milling is the last step coffee takes before being put in the burlap bags we are familiar with seeing in the US and Europe. The coffee has been processed at the farm or cooperative station, and now is ready to have the final parchment removed, sorted for quality, and bagged for its various destinations. These destinations, depending on the grade of the coffee, and the position it is in from sorting varies from the world’s commodity market to the specialty shops of Europe, Asia, and other specialty markets.

Like similar facilities around the world, this building is large. Extremely large. Somewhat dusty. Rather dark. And filled with coffee beyond comprehension. It takes less than ten minutes in one of these facilities to realize that the level of work that goes into coffee must certainly be underpaid, at least with regards to commodity coffee. We think we know a laborious side of coffee in the US… but we don’t. We really don’t. Here coffee is unloaded by hand from numerous trucks per day. Unloaded. Stacked. Moved. Re-stacked. Moved. Sent down into a large mill which removes the pulp or parchment. Sent through an optical sorter. Then to a conveyer belt which is lined with women hand sorting. Re-bagged. Moved. Stacked. Loaded again.

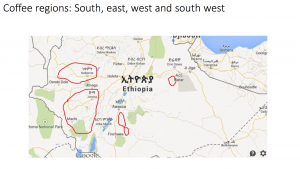

As a whole, Ethiopia is one of the top coffee-producing countries in the world, producing roughly 6.5 million bags of coffee per year. Interestingly with comparison to other large coffee-producing countries, Ethiopia keeps nearly half of that coffee in-country for domestic consumption. 90% of the production of Ethiopian coffee takes place on small shareholder farms. And approximately 15 million, or 15% of Ethiopians rely on the coffee industry for their income. Coffee is prevalent here to say the very least.

We travel towards the southwest of Ethiopia, first by plane, then by truck. We first stop at a home that serves as a post point for the owner of Limma Kossa Estate, Giday Behre, who established this farm in 2000 outside Jimma. We eat a lunch of injera served with a variety of spiced beans, lentils, and vegetables, and then are offered coffee. For coffee, we are introduced to one of the young women of the house who over the course of the next hour makes our coffee… from green, to roast, to brew…

Coffee carries a rich tradition in this country, and everyone seems to drink it. Not uncommon in the US either, but what is different is the importance placed around it and the respect paid to it. While in the US we are all too familiar with cheap gas station coffee and the Keurig, here in Ethiopia there is still a reverence associated with coffee. You can buy a coffee on the side of the road, but it is going to have just been roasted in a pan and is going to be served fresh. No matter how cheap the cup, you may have to wait a few minutes for it, and most likely it is going to be far better than anything any gas station in the US ever sees.

She builds a small fire on an open canister-bowl-charcoal-holder-thing that serves as a stove for roasting, a small sort of bowl that holds coals and she eventually heats a small pan over the top of. Green beans that have been soaking in water are strained and put in the pan. Using a small paper fan she fans the coals increasing the heat and stirs the beans over the course of the next fifteen minutes as the coffee roasts. At the point of the first crack everything is smoking ceremoniously and we all smile because we all recognize exactly what is happening even when we go about the process so differently. Expensive custom roaster or not, coffee is coffee, and great coffee is great coffee in the hands of people that know how to transform it into a brewable drink.

After pouring the coffee beans into a metal bowl to cool she retrieves a large mortar and pestle for grinding the coffee. Coffee grinds are added to a large, elegantly shaped brown earthen pot and steeped in boiling water for several minutes. This same process I will come to find is the same and different throughout Ethiopia. Like the US, everyone has their take on how to perfect the task, but the end result is common.

We take our coffee in several rounds of small glasses and sit under the shade tree watching as dogs lounge in the warm breeze rolling on it’s back in the bushes and as a trail of insects works its way up the side of the home to an overhang that seems full of insects I’ve never seen before. Watch out for ants, Abiy tells me.

We load our things in a Land Cruiser and head up towards the mountains. The small mountain road passes through small villages with open markets and stalls along the street. The smell of roasting coffee is intermixed with the smell of street life. As the road becomes steeper it becomes smaller and eventually, the pavement ends and we work our way into the rolling mountains. The hillsides are lush green with tall shade trees and only periodic openings where we can see the larger landscape beyond. In these few open areas we see cows in the pasture and people making their way around the forest carrying baskets. Coffee.

This area is rich with coffee. Naturally occurring. Even small residential huts have coffee growing around them. Everyone grows a little coffee. We enter a small valley, the low gear of the truck grinding higher, and a strong pungent smell erupts in my nose and I look over to see if anyone else notices. Monica explains that it is the result of a poorly executed wastewater system of some larger coffee operation. This came to be one of the issues most brought to my attention on this trip, the management of wastewater. I have come to realize that it is one of the largest environmental impacts along with the spraying of toxins that are associated with the growth of coffee.

After the coffee is washed, the fruit has to go somewhere. Often small piles of the mucilage are kept and dried and placed around coffee trees as a natural fertilizer, but regardless, large amounts of mucilage water have to be dealt with. On farms like the one we are driving through the water is simply put in the local creek to wash down, resulting in great dead zones from too many nutrients and rotting nutrients. The smell along with the hyper nutrition washes downstream and is left for others to deal with. This is considered a very poor, but common farming practice.

Things look very different on Limmu Kossa and any other certified organic farm. Part of the certification process involves wastewater management. Common and accepted practices are to build a large pool down below the wet mill that fills with the wastewater and overtime is allowed to filter through the soil before it reaches the water system. Vetiver is used in Ethiopia as a filter plant all around the water system to help pull the nutrients out of the water and help filter it before it flows down into the creeks.

On the top of the ridgeline, we travel several more miles, but the area slowly becomes increasingly wooded as we go. Monkeys appear in the trees overhead. We are arriving at Limmu Kossa Estate.

While 90% of the coffee grown in Ethiopia is grown on smallholder farms of one to two hectares, this is a larger farm of 356 hectares or approximately 750 acres. Coffee grows wild in this part of Ethiopia and cultivating the farm was more a matter of creating roadways, pathways, minor clearing, and building the infrastructure necessary for washed and natural coffees. At the farm, we see housing for farmworkers off to the northeast of the road, and a large coffee production area to the southwest, including a large barn, a covered washing station, and hundreds of drying tables. Along the small dirt road, we arrive on the side is covered in tarps, and a great bustle of harvesters is beginning.

Pickers are laying their harvest from the day out along the tarps in piles and sorting. They sort any green cherries out and put them into separate piles. After their pile has been approved for being amply sorted they can then take their load from the day up to the wet mill where it will be weighed and put into the washing cycle. The washing station will run through the night and in the morning the whole process will begin again.

We tour the farm over the course of the next few days, sleeping in tents in a cow pasture that is visited by baboons and other night creatures. The farm is not as much what we think of as an individual entity in the States, but rather a community of people varying from 150 – 400 people depending on the time of year. This is the busy season so there are people abound and daily harvesters working at bringing in the coffee crop. Coffee is a crop that is harvested slowly in rounds as each bean ripens, not necessarily at the same time on the trees.

On the Limma Kossa farm, we have access to every step of the production. Starting early in the morning the pickers gather at the collection point and are sent out into different lots of the farm depending on which areas are ready to be picked. The operations area of the farm then quiets for several hours while the pickers disperse through the farm before reconvening again the afternoon to sort their coffees out before taking them to the washing station.

Limmu Kossa estate recently built an additional three classrooms at the local school which allows for the local education of children between grades 1-4 without having to go the further distance to Jimma. Limmu Kossa is heavily invested in the community across many fronts. (Giday’s nickname is “Abba Olie” locally, meaning “the one who uplifts.”) Being the largest estate in the area they have been able to also help neighboring farms, most of them extremely small scale, but providing more than 350K disease-resistant coffee varietals over the years. They have finished several miles of road building and built a grain mill that is used by people from all around. All of this has led to them taking a lead role in teaching sustainable farming practices to the entire community and becoming a center point for people from around the area.

The washing station is relatively quiet for much of the day as the people running the machinery weigh and collect the coffees and put them into the vat that leads into the washing machine. Their responsibility is to make sure every pickers’ harvest is logged and tracked so that everyone is paid accordingly. Towards the evening the machinery, run on a gas generator, is fired up and run through the night. The coffee is sent through the washing station and put into large concrete vats where it will remain until the next day and is then drained and spread across a vast hillside covered in raised screened beds.

Throughout the day workers move around the hillside slowly turning the coffee by hand to allow for even drying. The coffees will dry like this for roughly 7-10 days, being covered at night to regulate the drying process and temperature, and then are uncovered again in the morning. From this point, the coffee is either in parchment if washed, or in full dried fruit if natural, and bagged to be sent down the mountain and across the country by truck to the dry mill facility in Addis Ababa. These facilities handle coffee from all over the country and have a thorough system in place to account for the various grades of coffee and have an extensive tracking system that allows for separation not only of the quality of coffee, but coffee by the farm, lot, grade, and certification. From here coffee is shipped to port and then off to market.

At night on the farm, the skies quiet as pickers and locals work their way back to their homes. We stay up late around a small fire watching the stars break through the light haze. At night I crawl in the tent and listen to a world of different sounds. At one point I hear what I suspect to be a baboon scratching the outside of my tent, but as I role over to make sense of what I am hearing I scare whatever it is off and hear the loud sound of it running back into the forest.

In the morning we roast coffee over a fire and make it slowly over the course of an hour. And this is perhaps one of the most unique aspects of visiting Ethiopia for coffee. The ceremony around coffee, no matter how casual or formal it may be, is just that. It is a genuine ceremony. There is pride taken in it at every level. And while so much of the world drinks coffee, few places have a population so directly intertwined not only with coffee that is exported, but that also use the same level of pride and connection with regards to their own daily cup of coffee. Colombia is an example of a country that takes great pride in the coffee that they produce, and rightly so, but they ship nearly all of their high-quality coffees out, and the majority of the country then imports coffee of lower quality from the likes of Nestle. Ethiopia, on the other hand, retains roughly 50% of its production in-country. It is not uncommon for people to simply grow all their own coffee in their yard. They roast it regularly and consume it with reverence. This is the magic of coffee in Ethiopia. There is a widespread connection to coffee. And even those that are not connected directly to, are indirectly by someone they know or work with.

On the way home from Ethiopia I took a coffee on the airplane for sake of juxtaposition. I couldn’t drink it. Something spoils you as you learn more about coffee and begin to realize it has everything to do with where and how and by whom it was produced. Quality coffees shine. They glow. You can taste the vibrancy. While so much of the world is drinking poorly grown and poorly processed coffee, there is an amazing leap forward happening in specialty coffee where not only are roasters paying more attention, but the growers are finding new and more effective ways to improve quality, and really, this is where good coffee comes from. Good coffee, like every other food we consume, starts with high-quality farming.

Beautifully written with nice pics. Really captured the excitement of travel, the curiosities of a new culture and the passion for a good cup of joe.

What a fantastic story! I went back in my thoughts to the wonderful time that we had together. You blended in with the locals and I rember people talking to you in local language, Afaan Oromo! you scared small kids though, just by looking at them…lol. Thank you for all the kind words, my friend.

Look forward for your next visit.

Abiy

Good read, thank you!

Thanks!